As lamentable as it may be, it seem that many contemporary kendoka give little serious thought to the true way of Kendo and its humanistic potential, and merely concentrate their efforts on learning how to defeat opponents through any means necessary for no other reason than for the sake of the sweet taste of victory.

This is not just the case with Kendo but many other budo arts which focus primarily on technique and self gratification through victory rather then the possibilities for character cultivation, despite their empty claims for the latter.

Anything with a “do” attached to it must place weight not only on the technical aspects, but also aim to forge the mind with the body so that both form a naturally balanced and rounded unity, taking the individual up another level in humanistic quality. This is the meaning of “do”. Concentrating only on technique is a sporting pursuit and becomes a purely egotistical exercise.

We have very often heard that the Samurai Sword is the soul of the Samurai.

How can an inanimate object posse a soul? In the hands of a technician the sword moves smoothly and with precision to the extent of his swordsmanship but when a swordsman develops to a much higher plane spiritually through intense training and study and he is able to hold the sword as if not holding it, the sword becomes identified with the man himself and becomes the extension of his inner self without any thoughts or emotions. The swordsman calls this unconsciousness “The mind of no mind” (Mushin no shin) Hence the soul of the Samurai.

The influence of Buddhism in budo cannot be overstated. One of the central ideals in Buddhism is that all creatures are equal. The life force in all living things is the same.

However humans must survive so we are compelled to take the life force of other things to go on living. From the Buddhist point of view we have naturally committed offences, even people who have gained power although it may be used for good has attained it though unavoidably committing some sin. The point is how this is dealt with. Is the perpetrator repentant? Are they fearful of the consequences? These two factors are the utmost importance.

Hayasghizaki Kansuke once said of the attitude essential after the “yaa†and “tou†of the first kata

“Even if your foe is greatly evil, don’t draw your sword, or let your foe draw theirs. Don’t cut and don’t be cut. Don’t kill, and don’t be killed. Help them transform into a good person. If they still won’t comply, then send them to the next world”.

The “yaa†and “tou†of ippon-me are not the result of the 3 poisons of Buddhism, (hatred, desire, and ignorance), but are the manifestation of right versus right. However, the result is death for the loser of the encounter, and such killing is the most serious of the cardinal sins in Buddhism. Penance for this act is required. It is thought that penance is a way of self help; it also refocuses the thrill of the fight to the thrill of the Buddhist way. This is a way of helping self and extends to helping others.

In Kenjutsu, the victor survives and the loser is killed. The victor, therefore, must engage in penance for the sin of taking the life of another.

This penance is the beginning of the Kenjutsu to Kendo metamorphosis.

So the zanshin demonstrated in ippon-me not only be a flawless posture, with situational awareness leaving no opening for reprisal be assumed, but also, Shidachi must feel a sense of penance for the act of theoretically taking the life of another in the clash of right versus right. This feeling of penance becomes entwined with the choice of technique utilised in nihon-me.

When Kendo Kata was devised it was created on the premise that ippom-me through to sanbon-me to be the teaching in schools and yonhon-me onwards take on an advanced educative role for the adult kendoka. Thus the first three Kata, jodan, chudan, and gedan are the terms used to describe the various kamae.

However from yonhon-me onwards, the term seigan was used to refer to chudan.

It remained so until 1981 when the Kata instructional manual was revised and there after seigan was known as chudan.

There were original differences between the two kamae, Seigan was higher and chudan lower this unification was not without it’s problems, as seigan had a deep meaning to the advanced kendoka. Seigan kamae is to the throat/eyes (So suba only is seen) Chudan is presented to the chest.

The reason for the mention of the difference of the two kamae is that seigan has a religious significance and a different kunji to write the word, literally translated as “right/correct eye”. The key word is eye and according to Buddhist tradition it is not only the physical action to look but also to know, to listen, and to understand.

The interpretation and concept of go-gen, or the 5 kinds of eye.

The eye of those who have a material body (niku-gen).

The divine eye of celestial beings in the world of forms. (ten-gen).

The eye of wisdom by which the two-vehicles observe the thought of non-substantiality. (ji-gen).

The eye of law by which the bodhisattvas perceive all teachings in order to lead human beings to enlightenment. (ho-gen).

The Buddha’s eye, the four kinds of eyes, enumerated above, existing in the Buddha’s body. (butsugen).

The “gan” in seigan corresponds with these five “gen” this is significant regarding the true meaning or spirit behind the kamae, it is representative of the Buddhist belief that Buddha-nature (correct heart) is inherent in all humans.

In nihon-me this is shown when shidachi strikes uchidachi kote. In the act of striking kote it reveals the spirit of seigan-no-kamae, the spirit of “jin” or sympathy/compassion. Therefore ippon-me “kill or be killed” for what one believes is right, nihon-me still has the same conviction, but is more advanced in that the goal is accomplished with more restraint, using technical skill without over kill.

This is the start of “butoku” or martial virtual.

Thus , Ippon-me represented by ’gi’ or righteousness is the way of people, Nihon-me represented by ’ji’ (compassion) is the way of peoples hearts.

This is taken to yet another level in sanbon-me., the technique is tsuki, but neither opponent touches each others flesh. Shidatchi has the control and uchidachi looks death in the face as shidatchi’s sword is placed right between the eyes. Instant death can occur. This situation goes beyond a simple win/loss situation. In fact, this is the ultimate truth in Kendo.

This is the moment of supreme reckoning shidachi kensen can dispose of uchidachi, but shows unequalled valour by not even touching the flesh.

Uchidatchi is reduced to the most humble and honest of life forms. After the instantaneous and inspirational period of reflection, both resume chudan and go back to the start. This is the true objective of the kendo way.

We now advance to a higher level and try to understand the Yin and Yang kamae.

Kata 4, 5, and 6 can be explained using the Yin-Yang theory.

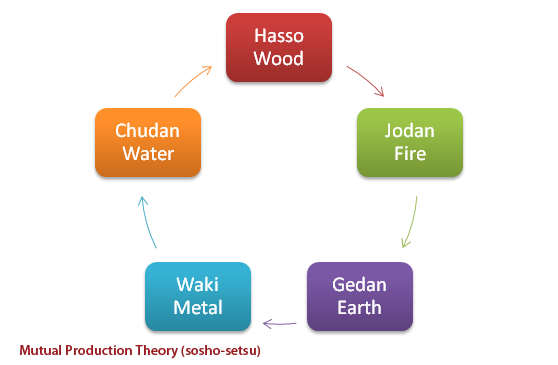

This is based upon the premise that the universe arises from the interplay of Yin and Yang, accompanied with the theory of the five phases (Go-gyo) i.e. wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. These 5 phases, or elements are to be understood as abstract forces that determine the course of natural phenomenon ( In Japanese as in yo go-gyo-setsu)

The five Constant Virtues (gojo) of human-heartedness (jin), righteousness (gi), propriety (rei), wisdom (chi), and good faith/trustworthiness (shin), are associated with the Yin-yang Five Phase Theory. These are even represented by the five pleats on the hakama. And this in turn can be equated to the five kamae found in Kendo.

JIN wood-spring-hasso. GI metal-autumn-wakigamae. REI water-winter-chudan

CHI fire-summer-jodan. SHIN earth-end of season (yo) gedan.

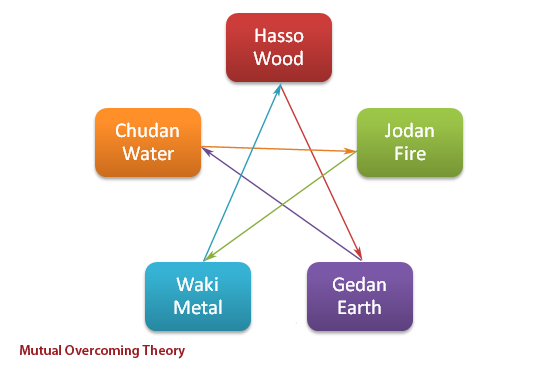

The Chinese philosopher Tsou Yen (305-240 BCE) devised the Mutual Overcoming Theory. This theory basically pits the destructive qualities of the Five Phases against each other:

Wood over earth, earth over water, water over fire, fire over metal, metal over wood, and so on.

YONHON-ME.

Uchidachi- hasso (wood.)

Shidachi wakigamae (metal)

Metal beats Wood.

GOHON-ME.

Uchidachi jodan (fire)

Shidachi chudan (water)

Water beats fire.

ROPPON-ME.

Uchidachi chudan (water)

Shidachi gedan (earth)

Earth beats water

Uchidachi then changes to jodan (fire) and Shidachi changes to chudan (water)

Water beat NANAHON-ME.

Kendo conducted in accordance with the principles of the sword (ken-no-riho) is ment as a means for character development, on both personal and societal level. Ultimately the goal is harmony at all levels. This was first expressed in 604 Japanese constitution article 1. Harmony is to be cherished, and opposition for opposition sake is to be avoided as a matter of principle. This is the philosophy which lies at the heart of nanahonme of kendo kata.

Uchidachi and shidachi both take chudan (water to water)

Uchidachi thrust to the chest shidatchi parries.

Uchidachi takes quickly jodan strike (fire)

Shedachi remains in chudan (water) cuts Do

Water beats fire.

The kata examined all indicate that they are manifestations of the spirit or ideals of kendo. These ideals raise kendo above the realms of techniques for killing or winning, but are a way of improving oneself. It also shows us a different way.

The clues are there in the forms and kamae, they may be difficult to decipher but it is important to take Kata seriously and look for them, it is a way of self-development to tap into the wisdom of old which has almost been forgotten.

Lets us now look at the Kodachi-no Kata.

There are two principles which lie at the base of the set of Kodachi kata which refers that long and short are one and the same. In other words, the merits and demerits are part of the same package. This can be applied both literally and figuratively to the three kendo kata. Upon reaching a certain level of mastery in kendo, one realises that both long and short sword has both merits and demerits, thus essentially it should make no difference to the adept weather they use long or a short sword. ideally you should be able to use the short sword to the same effect as a long one.

Let’s look at the Japanese words Chotan-ichimi which pertains to N0.1 and 2 of the kodatchi kata and Muto no kokoro (heart of no sword).to the No 3 the finial kata.

Average men mistakenly think that a long weapon is advantageous when compared to a shorter one, but great men understand the concept of chotan-ichimi, where long and short are realized as one and the same. In other words, in essence the length of the sword is decided by the strengths or weaknesses of the heart.

As we strive to sharpen our spirit with the testing blade of self reflection, we come to realise that within our hearts resides strengths and weaknesses, virtues and shortcomings.

These coexist as part of our being. These are the cho (length-strength) and the tan (short-weakness) of our heart. They are inevitable and co-exist in harmony.

Thus, in this sense it is futile to ponder the merits of the length of one’s weapon.

Accordingly, do not deliberate over issues of length, but throw yourself whole heartedly into the attack and you will achieve your purpose. In doing this the length of your sword will be in accord with the strength or the weaknesses of your heart.

Therefore short will become long and long will become short, and enlightened understanding will be attained that long and short, strong and weak are part of the same and inextricably tied together.

Muto no Kokoro (heart of no sword)

The sword is controlled by the heart, and the heart is not swayed in any way weather the sword is short or long there is no distinction, the spirit should not dwell on this fact, but assume that you have no sword at all. You must without hesitating seize the opportunity to throw your body and soul at your enemy, and without taking as much as a half step backwards go straight up to them and cluch their very essence and quash it. This is how to defeat the long sword with ease. The heart of no sword is the definitive aspiration of chotan-ichimi.

This I believe, very much applies to modern day kendo as well.

Ippon-me is coupled with the concept of shi and signifies gi or righteousness. Nihon-me corresponds to gyo and implies compassion (jin) Sanbon-me corresponds to (so) and connotes bravery or valour (yu) If you look at the kodatchi kata you can see the transgression clearly by taking note of the kamae, and timing of the final blows.

SHIN-GYO-SO.

Kodachi ippon-me Shin = Fell adversary with one cut.

Kodatchi nihon-me Gyo = Cut adversary after controlling them temporarily first.

Kodachi Sanbon-me So = Control adversary and attain victory without actually killing them.

Definitions

YANG; active, aggressive, or things in a state of progression. Light, hard, fire, summer, daytime, obverse/front, advance, revolving to the right, upward movement, movement on the right side.

YIN. Passive, defensive, or, things in a state of non progression. Dark, soft, water, winter, night time, reverse/back, backward movement, revolving to the left, downward movement, movement on the left side.

The five phases started out as an individual line of thought. The phases (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) are paradigms or analogies for specific modes of behaviour.

These were combined with the categorical system of yin and yang. The five phases were seen as moving through regular and predictable cycles of succession both in space and time. Yin and yang were two polar energies that, by their fluctuation and interaction, are the cause of the universe. Yang contains yin, yin contains yang, and the basis of the ten thousand things (wan-wu). Sometimes yang will appear, and at other times yin will emerge. This manifestation of all phenomena is seen as a cyclic process, an endless coming into being and passing away, as everything upon reaching its extreme stage, transforms into its opposite. The underlying shared characteristic of yin and yang therefore consists in giving rise to this continuous change.

For example, candle light during the day is yin, but would be yang at night.

There are many theories of five phases of yin and yang, so I would like to expound on one only The mutual overcoming theory (sokatsu-setsu)

TungChung-shu (104-179 BCE) was the main advocate of this theory where the five phases continually gave birth to each other, rather than cause destruction as in the other theories. Wood gives birth to Fire, Fire gives birth to earth, Earth gives birth to metal, Metal gives birth to water, and Water gives birth to wood, and so on.

The above is a basic outline of the complicated theories of yin-yang and the five phases. In kendo kata, we see, that Hasso is pitted against Wakigamae in yonhon-me, Jodan against Chudan in gohon-me, Chudan against Gedan in roppen-me.

In applying these combinations to the yin-yang five phases we see that the above diagram is the most representative.

The yin-yang five phase theories have their basis in natural phenomenon, and the propagation of these theories over many centuries has had a profound effect on Japanese culture. Today such philosophies make way for modern science and technology, and ancient knowledge takes a back seat eventually falls into total obscurity. Regardless of all modern wonders and science, it is important not to forget or overlook the wisdom of the ancients. Such can be found in one form in the kendo kata, if practitioners cared to look. This makes it a valuable resource worthy of more attention.

The Japanese of old placed much emphasis on these principles in many other facets of traditional culture and thoughts as well. Indeed, there are many lessons which can be gleaned from such wisdom and still applied to everyday living by us moderns.

In this sense, it is important that we are able to utilize Kendo to its full potential by having an understanding of these principles that lie behind the philosophy of Kendo Kata. This is where we are able to embark on the DO- the way of Kendo.

John Howell

7th Dan Kyoshi

February 2010

Acknowledgments

From the teachings of Yoshihiko Inoue Sensei and Daisetsu Teitoro Suzuki Sensei and the book Kendo Kata, Essence and Application. Author Yoshihiko Inoue Sensei Translated by Alex Bennett.